Deprecate. Fix. Enforce. Repeat.

lint , evolution , deprecations

Software quality doesn’t improve because one day we decide to run a massive refactor.

It improves when we build a system that prevents the code from getting worse and gradually, almost inevitably, pushes it to get better.

Linting, when used strategically, can become exactly that system.

Not a tool to argue about semicolons. Not a stylistic checklist. But an evolutionary mechanism.

Let’s walk through a concrete TypeScript example and see how a codebase can evolve over time.

The Starting Point: Code That “Works”

Imagine we have this function:

export function calculateTotal(items: any[]) {

let total = 0;

for (var i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

const item = items[i];

if (item.price) {

total += item.price;

}

}

return total;

}

Does it work? Yes.

Is it ideal? Not really.

Issues:

- It uses

any - It uses

var - It has no explicit return type

- It relies on weak checks

- No architectural constraints protect it

This is the kind of code that often grows organically and then stays around for years.

The question is not how to judge it.

The question is: how do we improve it without stopping the team?

Phase 1 - Declare What We No Longer Accept

The first step is not fixing everything.

It’s declaring what is no longer aligned with our future standard.

We configure ESLint like this:

{

"rules": {

"no-var": "warn",

"@typescript-eslint/no-explicit-any": "warn",

"@typescript-eslint/explicit-function-return-type": "warn"

}

}

We are not breaking the build.

We are not blocking releases.

We are simply making technical debt visible.

From now on:

varis not our standardanyis not our standard- implicit return types are not our standard

A warning is a promise:

This works today, but it does not represent the level we want tomorrow.

Phase 2 - Improve Incrementally

Now discipline matters.

No big refactor required.

Just one simple rule: clean as you touch.

If you modify a file, you fix its warnings.

This is just a way to approach this problem, there could be other ways, but we’ll see them in another article.

First, remove var:

export function calculateTotal(items: any[]) {

let total = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

const item = items[i];

if (item.price) {

total += item.price;

}

}

return total;

}

Then remove any by defining a proper type:

interface Item {

price: number;

}

Update the function:

export function calculateTotal(items: Item[]) {

let total = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

total += items[i].price;

}

return total;

}

Finally, make the return type explicit:

export function calculateTotal(items: Item[]): number {

let total = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

total += items[i].price;

}

return total;

}

We didn’t rewrite the system.

But we:

- removed unnecessary dynamism

- improved readability

- increased type safety

Multiply this process across months, across PRs, across a team.

The impact compounds.

Phase 3 - Promote to Error

Once a rule has been fully cleaned up, something important happens.

We promote it from warn to error.

{

"rules": {

"no-var": "error",

"@typescript-eslint/no-explicit-any": "error",

"@typescript-eslint/explicit-function-return-type": "error"

}

}

From this moment on:

- No new

any - No new

var - No implicit return types

CI blocks regressions.

Improvement becomes permanent.

This is when the team’s standard truly changes.

It’s no longer a recommendation.

It’s enforced.

Phase 4 - Raise the Bar

Once one standard is stabilized, we can raise it.

For example:

{

"@typescript-eslint/strict-boolean-expressions": "warn",

"complexity": ["warn", 5]

}

The function might evolve into something like:

export function calculateTotal(items: Item[]): number {

return items

.filter((item) => item.price > 0)

.reduce((acc, item) => acc + item.price, 0);

}

Less mutation.

Lower complexity.

More expressiveness.

When violations are resolved, we promote those rules to error.

And the cycle continues.

The Critical Role of CI

Here’s a simple truth: If quality isn’t automated, it will eventually be ignored.

Many teams do this:

eslint . --max-warnings=0

It looks perfect.

But there’s a subtle issue.

If you permanently enforce --max-warnings=0, you prevent yourself from introducing new rules as warn. The moment you add a new rule, existing code will generate warnings and CI will fail immediately.

That’s not what we want.

We want to:

- prevent regressions

- allow controlled evolution

Freeze the Baseline

A more mature approach looks like this:

- Run ESLint and count the current warnings.

- Set that number as the maximum allowed.

- In CI, fail only if the number increases.

For example:

eslint . --max-warnings=120

If today you have 120 warnings, CI accepts 120 or fewer.

But 121 fails the build.

This changes the dynamics completely.

You can:

- introduce new rules as

warn - migrate gradually

- lower the threshold over time

Quality doesn’t need to be perfect immediately.

It needs to be monotonically improving.

When --max-warnings=0 Makes Sense

Zero warnings is appropriate in specific moments:

- When a migration is complete

- When a category of problems has been fully eliminated

- When a rule has been promoted to

errorand no warnings remain

Zero warnings is a phase in the cycle.

It is not a permanent philosophy.

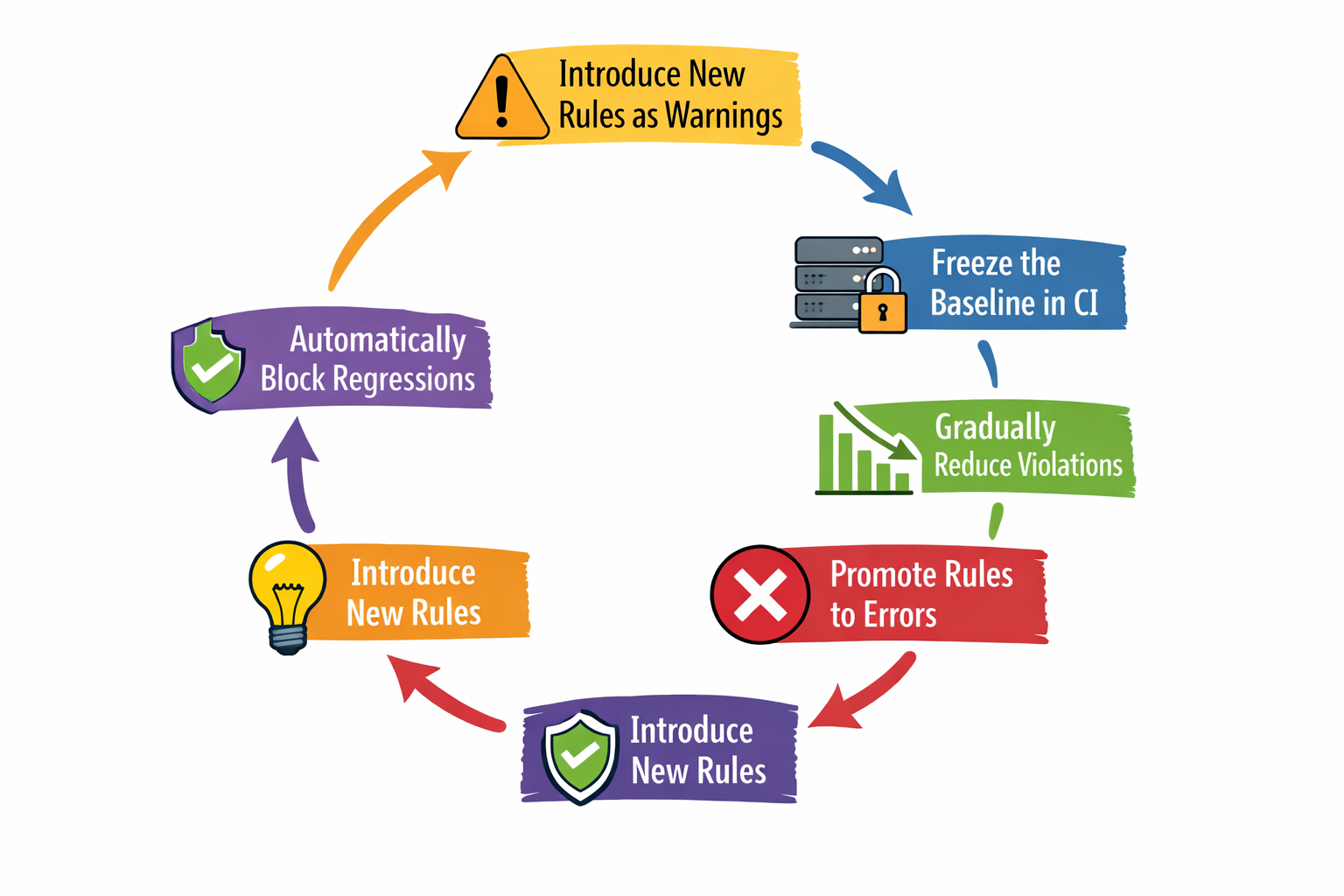

The Evolutionary Loop

The full model becomes:

- Introduce new rules as warnings

- Freeze the baseline in CI

- Gradually reduce violations

- Promote rules to errors

- Automatically block regressions

- Introduce new rules

Repeat.

No heroic refactor required, just a well-designed evolutionary system.

This is quality with compound interest.

Today you remove an any.

Tomorrow you ban var.

Six months later, your codebase is more predictable, more readable, more robust.

Not because someone rewrote everything.

But because you built a system that makes improvement inevitable.

Linting is not just about style.

It is a tool for technical governance.

If it stays static, your quality stays static.

If it evolves, your codebase evolves with it.

Deprecate.

Fix.

Enforce.

Repeat.

That’s how quality stops being an abstract goal and becomes a natural consequence of the process you chose to build.